Why “Just Train More Dentists” Won’t Fix the UK Dental Crisis (and What Will)

Training more dentists is part of the answer—but only if we fix the system they enter.

The other day I found myself in a dental chair across from a familiar face, a brilliant graduate from my Dundee teaching days who now mentors new dentists in her practice as part of the Dental Foundation Training programme. Over lunch, we compared notes. She spoke about the reality of bringing fresh graduates into her general practice; I spoke about education and training to get our students to ready for the world of practice, as a Dental School Dean.

I’m regularly asked the question: “If there’s a shortage of dentists, why don’t you simply train more? After all, there are scores of applicants for every place.” On the surface, it feels as if the answer should be that simple. It isn’t. This post explains why and sets out practical, near‑term solutions that would improve access faster than expanding dentist numbers alone (the information sources I’ve used to write this, are all at the end of the piece).

Two truths at once

1) Training dentists well takes time, people, places and money

A modern dental degree blends science and simulation with carefully supervised clinical care. Students learn in labs (including “phantom head” simulators), repeat procedures until they are competent, sit rigorous assessments, and then treat real patients, always under close direct supervision by qualified clinical academics and experienced practitioners. This isn’t bureaucracy; it is patient safety and how we develop excellence.

2) The pipeline is long and tightly regulated

A Bachelor of Dental Surgery is typically five years. Even if we expanded the number of places tomorrow, graduates would not reach practice for half a decade. Program length matters here: look at any BDS course page and you’ll see five years before Dental Foundation Training begins (the students qualify and enter the profession with a mentor, such as my friend). This is almost universal across the globe

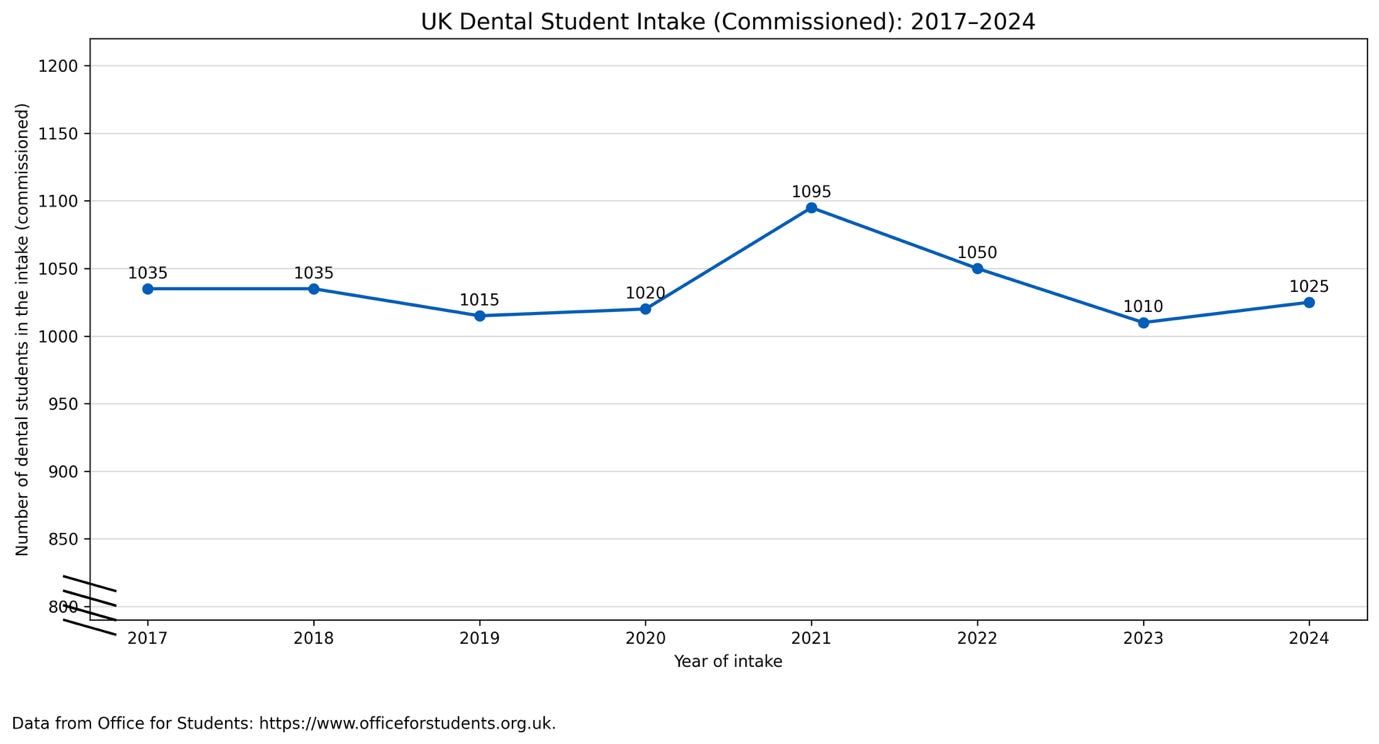

Dental schools cannot unilaterally expand in the UK anyway as dental student numbers are capped by government and tightly commissioned to align with workforce planning and funding.

In 2024/25, the confirmed intake across UK dental schools was ~1,115, governed by the Office for Students and health departments to ensure enough clinical placements and supervision.

What constrains dental schools right now?

• Applicants far exceed funded places, but capacity is finite. There is no shortage of interest. In 2023, there were over 10,000 UCAS applications for around 940 dentistry places.

• Safe supervision isn’t optional. GDC Standards for Education (rightly) require schools to prove safe staff-to-student ratios for clinical care and assessment. Scaling numbers without proportional increases in appropriate staff and clinic space would fail those standards and, more importantly, risk patients.

• Thinning pipeline of clinical academics. In the UK, more clinical academics are retiring than being replaced, which is threatening future training capacity. Clinical academics hold a unique set of clinical and educational skills, essential for creating curricula, supervising students, delivering education, and supporting research. According to the Dental Schools Council, 25% of clinical academics are aged 55 or over, and 57% of professors fall into this category, highlighting an ageing workforce and a looming skills gap. Without targeted investment in recruitment and retention, this shortage threatens the quality of dental education and the ability to expand student numbers.

• Clinical space and team shortages are real. We need dental chairs, materials, specialist equipment and dental nurses, a precious resource, critical in supporting and training students but in short supply too.

• It costs far more to train a dentist than the tuition fee implies. Home students pay just under £10,000 per year (and of course with accommodation etc the average dental graduate departing university in 2021 had accrued £53,000 debt) , but the true cost is many times higher, underwritten by government high‑cost teaching grants and clinical placement tariffs. The Department of Health and Social Care has estimated the total cost of training a UK dentist at around £292,000. Without matched funding, rapid expansion simply isn’t viable.

• Universities’ finances are stretched. Even before any expansion, universities are navigating rising costs, greater support service demand and lower cross‑subsidy from international students. Dentistry is among the most expensive courses to deliver, requiring ongoing capital investment to keep clinics safe and modern. The Office for Student’s funding guidance and maximum‑intake controls exist precisely because of these high costs and the need to protect quality.

• Even when we train more, many drift from NHS work. The shrivelling of NHS access is not just a pipeline issue; it’s a contract issue. Independent assessments found recent, limited tweaks (new patient premiums, mobile vans, “golden hellos”) have not fixed the fundamentals. The National Audit Office and Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee concluded that the current NHS dental contract remains unfit for purpose, with insufficient incentives for NHS care, contributing to workforce leakage into private work.

Meanwhile, patients are feeling the squeeze.

National Audit Office statistics show ongoing access problems: for example, only about 40% of adults in England saw an NHS dentist in the two years to March 2024, while unmet need is estimated at around 13 million adults and 4.7million fewer courses of treatment were provided through NHS dentistry in 2023/24 compared with 2019/20. That problem won’t be solved by training alone, certainly not quickly and this is not a new, unexpected problem.

So, what will help now but will also be sustainable?

1) Fully deploy dental therapists and hygienists (DTHs)

They can already provide a wide range of care under direct access rules, but NHS systems often block them from opening and closing courses of treatment or being paid properly for prevention and periodontal care. Fixing this would unlock capacity immediately.

2) Reform the NHS dental contract, without losing continuity of care

Here’s where caution matters. Some recent reforms, and in Wales, proposed reforms, unintentionally fragment care. Patients are treated as one‑off cases rather than having a “dental home” with continuity over time. That undermines trust, preventive care, and early detection of disease.

Continuity matters because dentistry isn’t just about fixing teeth, it’s about monitoring oral health over years, spotting systemic disease, building relationships that support prevention and monitoring the success of individual responses to treatments. In the case of children growth and development of the teeth need to be kept under surveillance over time. A contract that incentivises episodic care risks eroding these foundations.

Scotland’s 2023 NHS dental contract reform replaced the old item-of-service model with a streamlined system of 45 treatment codes, aiming to simplify claims, reduce bureaucracy, and give dentists more clinical freedom. However, early evidence suggests these changes have not yet shown the hoped for, big improvement in patient access. Registration remains high at around 94.6%, but participation (the number of people actually receiving care) has not significantly increased, and inequalities persist, with adults in deprived areas still attending less often. Surveys show only 7% of dentists believe the reforms have improved access, and most warn that without further changes, the system will not reverse the trend toward reduced NHS availability.

3) Align training with the care model we want

There’s a growing dissonance between the safety‑net model emerging in NHS dentistry (where the focus is on urgent, episodic care only when needed) and the comprehensive training dentists receive. We train graduates to deliver excellence across the full spectrum: complex restorative work, prevention, patient management, and long‑term care. If the NHS offers only a narrow slice of that, we risk wasting money in training, demoralising new dentists and accelerating the drift to private practice where comprehensive patient care can be provided.

4) Back the Dental Schools Council’s plan to expand smartly, not thinly

In Fixing NHS Dentistry (endorsed by all UK dental schools), DSC sets out a practical blueprint: increase places in dentistry and dental hygiene/therapy, invest in clinical academics, fund placements properly, build regional training hubs in “dental deserts”, and provide capital for chairs, kit and infection‑control‑compliant clinics. It also calls out the ethics and fragility of relying on overseas‑trained professionals while under‑training domestically.

Concretely, that means:

• Define and fund new training numbers across all four nations with matched capital and staffing, not just lift caps on paper. (The Office for Student’s maximum‑intake controls exist to prevent unfunded growth that would erode quality.)

• Invest in clinical academic careers (protected time, fellowships, pay progression) so we have enough supervisors to teach safely.

• Ringfence placement funding for DTHs, whose programmes are especially vulnerable to tariff shortfalls.

5) Prevention at scale

Commission and pay for prevention delivered by the whole team. This includes fluoride varnish, toothbrush and interdental cleaning skills development for patients, risk‑based recall, smoking cessation and individualised behaviour change support . But not as an afterthought but as a core service.

Why dental schools can’t “just take more students” tomorrow

• Quality and safety standards. The GDC obliges us to prove safe staffing and supervision. You cannot double clinical years without doubling supervisors, dental chairs, material's, laboratory technicians and facilities and nurses.

• Funding reality. Home fees cover a fraction of the cost. Grants and placement tariffs bridge the gap. DHSC estimates ~£292k per dentist trained; if the gap isn’t funded, growth simply shifts costs onto already strained universities and health services.

• National caps and alignment. Intakes are commissioned nationally to match downstream training slots and service need; recent intakes have been ~1.1k per year. Sudden unilateral growth would break the clinical placement system.

• Time lag. Even if new places are funded this year, the earliest impact on head‑count in practice is five years away. Meanwhile, without contract reform, newly minted dentists may still shift toward private work.

What you’d notice if we got this right

• Faster NHS access for routine prevention and periodontal care, because DTHs can book, treat and complete NHS courses of treatment within scope.

• More care delivered closer to home via outreach training hubs in underserved areas.

• Clearer, simpler NHS treatments with fairer rewards for prevention and complexity, akin to Scotland’s streamlined approach.

• A sustainable training pipeline: funded chairs, nurses and supervisors, and protected clinical‑academic careers, so quality doesn’t drop as numbers rise.

• Less firefighting in urgent care, as prevention reduces disease burden.

A final thought from that lunch

My former student spoke about the pride of watching new graduates grow into calm, capable practitioners, with a great hygienist and therapist at their side and about the fantastic work ethic she has seen in the young dental nurses that have recently joined her practice. That’s the profession we should build around: a full team, working to the top of their skills, in a contract that values prevention and complexity, and a training system that grows smartly, not thinly.

Expanding dental places will be part of the answer. But if we don’t fix how we commission and fund care, and if we don’t unleash the tremendous potential of dental therapists and hygienists, we’ll keep pouring excellent graduates into a leaky bucket. The solutions are in reach; the will to implement them must follow.

Information sources

· https://www.nao.org.uk/reports/investigation-into-the-nhs-dental-recovery-plan/

· https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5901/cmselect/cmpubacc/648/report.html

· https://www.bda.org/media-centre/13-million-unable-to-access-nhs-dentistry/

· https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/statistical-collections/dental-england/dental-statistics-england-202324

· https://www.sdmag.co.uk/2023/12/08/start-of-a-journey/

· Buckland E, Barnett R, King T, Whitehead P, Blaylock P. Student debt of UK dental students and recent graduates. Br Dent J. 2023 Feb;234(4):260-266. doi: 10.1038/s41415-023-5531-4. Epub 2023 Feb 24. PMID: 36829020.